serious git thinking

I have been a git user for 513 days.

When I was first setting up this blog, my dear friend Charles T Gray helped me learn the 3 terminal commands that you need to know to interact with git in the most rudimentary of ways.

git add .

git commit -m “something meaningful”

git push

Since then I have mostly just used these 3 commands to push blog posts to git. In fact I don’t even really remember the commands (i.e is it commit dash m? Or commit m dash?), because my terminal remembers for me! I just use the up arrow to scroll through recently used commands.

But git is really supposed to be helpful for version control and collaboration. So… it is time to broaden my git horizons.

Luckily Charles and I had an opportunity to collaborate on a project recently and we did it with branches and pull requests and even one instance of a insurmountable merge conflict that resulted in us just burning it all down (which is fine because it is version control).

In this post, I am going to try and replicate what we did by inviting Charles to “fork” a copy of my blog repo and contribute to this post in a “branch” that we will “merge” (I think those are the right terms, but definitely correct them Charles!). Along the way, hopefully we will create a walkthrough that will be a useful resource for others trying to learn git.

when things go wrong, it is ok to just burn it down

The scariest thing about git is the error messages. Just tonight I ran into a branch merge error on my own blog repo, which is weird because I am the only person who works on it and I don’t even know how to create a branch… sigh.

Git errors are impenetrable. The hints are not helpful and the word fatal just makes it sound really bad.

N591:RnotesBlog jenny$ git pull error: Pulling is not possible because you have unmerged files. hint: Fix them up in the work tree, and then use ‘git add/rm

’ hint: as appropriate to mark resolution and make a commit. fatal: Exiting because of an unresolved conflict.

But what I have learned from troubleshooting this, my second merge conflict this week, is that it is ABSOLUTELY fine to burn it all down and clone again. To be clear… this means deleting the local copy of your repo and then cloning from github. Don’t delete your repo on github!

That's what I do! pic.twitter.com/97fdxsuAKp

— Michael Sumner (@mdsumner) November 12, 2019

Charles held my hand through this process tonight on slack and it is relatively painless. I even learned a little bash along the way.

how to use bash to burn it down and reclone

- open a new Terminal

- type

pwdto print your working directory - navigate to the location of the repo you want to burn using

cd path/to/where/you/want/repoto change directory. You don’t need to type the file path. You can just type the first letter of each folder level and use tab to auto-complete (handy!) - once you are at the folder that contains the repo you want to delete (check using

pwdagain) check that the folder you want to delete is there, usinglsto get a list of contents. - then type

rm -rf old-repoto remove the folder and everything in it (rf is for recursively forcing) - use

lsto check that it is gone

AND THEN… this bit will blow your mind…

…go to your github repo and copy the url that is displayed when you press the green Clone button. Back to the terminal and type git clone paste-url-from-git to clone your unconflicted repo.

It is almost so easy to burn it down and clone again that I am less motivated to learn how to actually deal with merge conflicts than I was yesterday… BUT this is what this project is all about.

I am going to push this post to my blog, Charles is going to fork it and then contribute something about her git journey thus far…..

Over to you Charles!!

people who know git: if it all goes terribly wrong you can burn it to the ground and start again. Because it’s version control... Watching @cantabile do this to our repo over lunch is strangely liberating #AIMOS2019 pic.twitter.com/vWSGf7xEyh

— A/Prof Jenny Richmond (@JenRichmondPhD) November 8, 2019

Musings from Charles on gitflow

walking around lappy486

All week I was thinking about what I’ve figured out about Git and it feels like nothing much at all.

What was interesting about working with Jen was how much she, too, valued the ability to burn it down and keep on going. Sharing my work collaboratively online is, right now, more useful to me than how adept I am at navigating versions.

And that takes me to some mathematical thoughts.

Jen and I made some progress in navigating these systems, and I think, for us, researchers who use code. We are research software engineers, our research is not focussed on code.

So what do we value? Well, as a graduate student, sharing code and creating online content, blogs and sites, has been of extraordinary benefit.

For this project with Jen, we set up a site the R package distill::, and deployed it via GitHub pages. In this context, that was more valuable to me than the version control itself.

So, if the focus is sharing, what is a minimal gitflow?

Finding our way around. A very good place to start.

grid-based navigation in *86 adventure games

In the eighties there was a golden era of puzzle adventure games: Monkey Island, King’s Quest, Space Quest, etc. We played these on 286, 386, and 486 machines.

Your screen would represent one grid square, and you could walk in four directions: up, down, left, right. This would take you to another place on the grid.

A little homework, @JenRichmondPhD; to whet your appetite for my contribution to our blog post. https://t.co/dqLiKhZXYg

— Cap'n Blackheart Bette (@cantabile) November 13, 2019

And I assume @Hao_and_Y and @Quasilocal will enjoy this task, too.

Navigating a computer is a similar experience. Your representative in the computer space changes location with respect to the computer space, even though you are still sitting in the same chair.

the seven bridges of königsberg

These grids were not infinite; indeed they were rarely greater than 10 x 10. When you reached a left edge, you could not move left any further.

There are two things to consider, places you can be and if two places are connected.

In 1736, Leonhard Euler transformed problems such as this when considering the problem of the seven bridges of the city of Königberg. The challenge was to devise a walk through the city that would cross each of the bridges once and once only.

](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5d/Konigsberg_bridges.png)

Figure 1: The bridges problem. (Image source [wikipedia).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5d/Konigsberg_bridges.png)

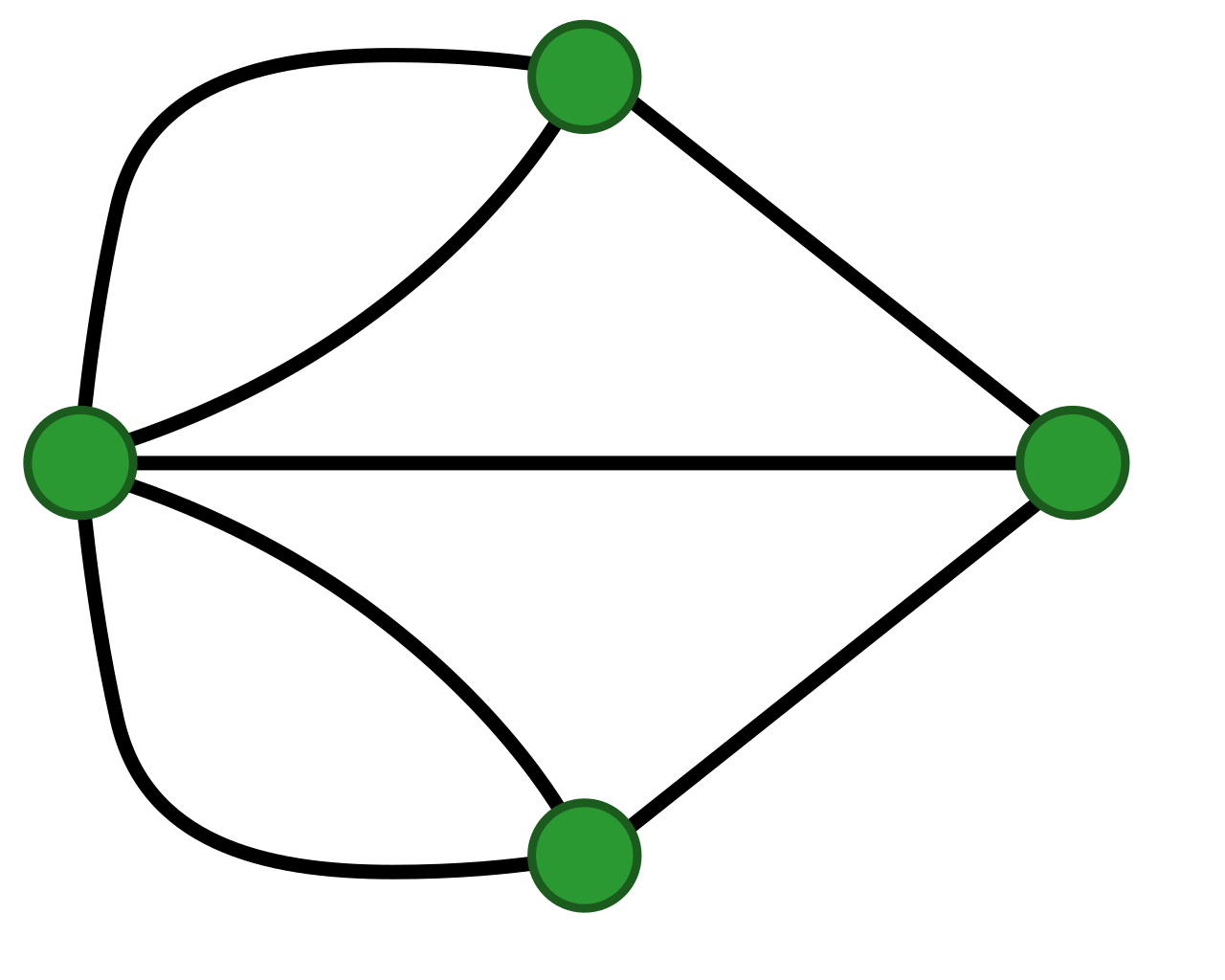

Euler reimagined this problem in terms of nodes to represent land and edges to represent the bridges. Or, as I refer to them in my head, bobbles and lines. Through this reimagining, Euler was able to show there was no solution to the problem of the bridges of Königsberg.

](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/96/K%C3%B6nigsberg_graph.svg/1280px-K%C3%B6nigsberg_graph.svg.png)

Figure 2: Euler's reimaging of the bridges problem. (Image source [wikipedia).](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/96/K%C3%B6nigsberg_graph.svg/1280px-K%C3%B6nigsberg_graph.svg.png)

These collections of nodes and edges are called graphs.

trees and git

The specific type of graph we encounter in navigating bash and Git, is a tree.

](http://mathworld.wolfram.com/images/eps-gif/Trees_600.gif)

Figure 3: Examples of tree structures with different numbers of nodes. (Image source [wolfram).](http://mathworld.wolfram.com/images/eps-gif/Trees_600.gif)

Trees are special types of graphs where you can’t go in a circle. They are acyclic.

Keep going down, and you will hit a bottom, and keep going up and you will hit a top. But they may not be the bottom or top you are looking for, and therein is the rub.

If I’ve learnt anything from this adventure in collaborating via git, it’s find a friend to walk these paths. Because, even though we can’t technically go around in circles, it sure feels like we are.